THE BELEURA - WORLD'S FIRST 108 KEYS

|

|

|

RECORDINGS

Faust: a Mortal’s TaleMortality has become somewhat the global theme of 2020 through the disruption of norms and questioning of one’s reality and existence. In essence, so too is the tale of Dr Faust, a human struggle of temptation and realisation of the unknown. Faust: a Mortal’s Tale draws its inspiration from the silent film ‘Faust’ (Murnau, 1926) and is a personal musical reflection of this story:

Journey HomeJourney Home is a new soundtrack release from renowned pianist Andrea Keller, composed by the musician in response to an exquisite film by Hayley Miro Browne.

This creative screen and sound collaboration is a tribute to each artists’ fathers, now deceased, combining music and film in mutual accompaniment. Andrea Keller’s music and Hayley Miro Browne’s visuals bring together images of Australia and the Czech Republic during the 1970s and ‘80s, captured through the lens of the pianist’s late father, Erik Keller. The compositions and improvisations presented in Journey Home were recorded over two days in early 2020, and in two locations in Victoria, Australia: Tempo Rubato, Brunswick and Beleura, Mornington. These two iconic venues were selected because they house three exquisite Australian made Stuart & Sons pianos, each with a distinctive timbre, touch, size, and range (from 102 – 108 keys). |

Two Deep BreathsReleased on 7 July, 2019, recorded with Ashley Hribar on pano with cellist Richard Vaudrey during a three day creative lock in at the iconic Tallis Pavillion, Beleura House (AUS) using two hand-crafted Australian-made Stuart & Sons pianos, (108 + 102 Keys), a 1791 William Forster cello, a Moog DFAM drum machine plus a collection of digital and analog effect pedals. Sleeping Orchards is a collection of twelve breathtaking improvised tracks forming their debut album by "Two Deep Breaths".

|

Rare ViewThis album consists of 13 new works recorded live at Beleura House’s Tallis Pavilion. This is the world’s first live album recorded with SONY’s brand new C100 Hi-Resolution microphones. Composed by Alan Griffiths and recorded with internationally acclaimed concert pianist Nicholas Young, Polish concert violinist Dominik Przywara and Australian concert cellist George Yang. Rare View is dedicated to the late Paul Martin, a dear friend of Alan’s

|

First 108 key piano released September 2018

The first 108 key acoustic piano was completed in September 2018 by Stuart & Sons in their Tumut, NSW workshops. This ground breaking achievement reaches the frequency realms of many pipe organs: C0 (16Hz) to B8 (7902Hz) and sets a totally new key range or ambitus standard for piano keyboards in the 21st century. The hitherto unimaginable goal of nine octaves has been realised after 300 years of piano development enabling the performance of all known compositions written for the instrument without frequency compromise. Music has been and will be written specifically for the whole nine octave range and as such, Stuart & Sons is proud to have created an instrument that is capable of rendering this material.

During the evolution of musical instrument manufacture never, in any previous period in time, has there been access to as many new materials, engineering capabilities and innovation. Stuart & Sons have taken the opportunities presented in these developments, rewritten the rule book, and designed and produced the first nine octave acoustic piano for the 21st century and beyond.

"WHY EXTEND THE RANGE OF THE PIANO"

An article written by French Technician Paul Corbin

[email protected]

From the very first four-octave fortepiano to the modern piano with its 7¼ octaves, the keyboard range has never ceased to increase... until 1880. As we shall see in this article, the 88 notes of the standard range have to be questioned, today more than ever. Many piano makers have been studying the problem, and yet pianos with more notes remain almost anecdotal nowadays. This debate which has arisen many times still causes doubts, and opinions are quite often divided. Why was the 88-note standard established, and is it sufficient to play everything? Why does the addition of a few keys repel and frighten pianists as well as technicians? What are the advantages of such an addition? Is an extended tonal range a mere gadget for the piano, or is it truly essential?

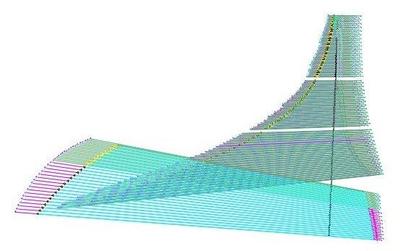

A Brief history of the keyboardThis timeline is only approximate. It represents the broadening of the tonal range of grand pianos in the course of time. It is hard to be precise, for this evolution depends on the manufacturers' geographic location. The German, British and French schools had different priorities and some preferred to add keys in the bass, some others in the treble, others still did not necessarily care and often ended up behind the times compared to their competitors. To number pitches, I shall use the ‘scientific’ system, the lowest pitch being A0 and the highest one C8 . The term ‘tessitura’ being suitable for the human voice only, I shall use the words ‘ambitus’ or ‘tonal range’. According to the musical instrument inventory of Ferdinand de Medici established in 1700, the first ever piano designed by Cristofori had 49 keys, that is four complete octaves, ranging from C2 to C6 . Today, the three surviving Cristofori pianos prove this description correct, even though the oldest one has been subsequently altered(1) . Around 1775, in the middle of the Classical era, the piano range reached five octaves and remained unchanged for nearly twenty years. The first pianos exceeding five octaves were built around 1790, and the standard was established about five years later. Their ambitus encompassed from F1 to C7 . From the 1810s onwards, six-octave keyboards became common. On the one hand, the British chose to extend the range in the bass (C1 to C7 ), and on the other hand, Germans and Austrians choose to extend the keyboard in the treble (F1 to F7 ). From 1820 onwards, piano makers did more or less as they chose, and it is hard to establish a rule applying to everyone. It can at least be said that all keyboards now exceeded six octaves. It was the piano maker Henri Herz who, from 1831 onwards, was the first to build seven-octave pianos. Besides, they got a rather mixed reception(2). Within twenty years, each at his own pace, all piano manufacturers progressively reached seven octaves, that is 85 notes. The last three notes (A#7 , B7 and C 8 ) were added in the last quarter of the 19th century. In 200 years' time, the keyboard gained 39 notes, that is one note every five years. Yet we have stopped at seven ¼ octaves (88 notes) for more than 130 years. What happened to piano makers and pianists that could explain such a long stagnation? What made everyone agree on that standard? Is it still possible to extend the keyboard today, either in the bass or in the treble?

|

Comparison between the ambitus of Cristofori's keyboard and that of the modern piano

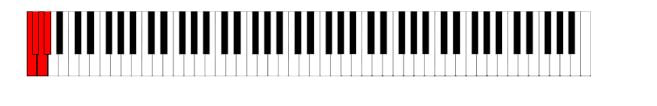

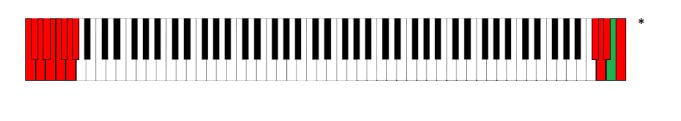

Pianos with more than 88 notes

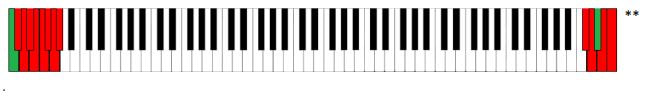

There are a few pianos whose tonal range exceeds 88 notes but that only represent a tiny minority, the most famous of which being the ‘Imperial’ Bösendorfer. After some research, the list has extended little by little, and even though it remains very small, all these pianos deserve the following few lines. This list is not exhaustive and it is highly possible that I have missed some piano models. In order to clarify reading, I shall use keyboard diagrams to represent their tonal range. Keys in red correspond to extra notes.

90 note:

As far as I know, seven piano models have 90 notes: model No. 3bis made by Érard from 1877 on (2m60), which became model No. 3 from 1903 onwards, models FI-24 and F-V by Ibach (2m75 and 2m70) which are no longer made today, the concert model built by Kaps at the beginning of last century and finally the concert model produced by the Philippe Henri Herz Neveu & Cie firm from the 1860s onwards. All these pianos go down to G0 .

92 note:

The only four pianos with 92 notes that I know of are models 225 and 275 built by Bösendorfer, as well as a few concert models by Petrof and Mand-Olbrich. They go down to F0 . The Bösendorfer 275 is, however, no longer made today.

97 notes (8 octaves) with extension in the bass only:

The Érard No. 80774, the Rubenstein R-371 and the Imperial Bösendorfer have 97 keys. The extra notes are located only in the bass, so these pianos go down to C0 .

97 notes with extension in the bass and treble:

The big grand piano made by Pape in 1844 as well as some models made by Stuart & Sons in Australia have 97 keys too, with extra notes in the bass and in the treble. Therefore they go down to F0 and up to F8 . The sole Érard piano model 3ter No. 51700 has 97 keys too. Nevertheless, it is not known whether they are located in the bass or in the treble.

102 notes:

The only pianos with 102 keys are the Stuart & Sons in Australia (both the 2.2m model and the 2.9m model) as well as Stephen Paulello's Opus 102. These pianos go down to C0 like the Bösendorfer and up to F8 like Pape's. Finally, some pianos had a few extra strings which were not struck but only served to move away the extreme notes from the edge of the bridge. It is the case, for instance, of Franz Liszt's Boisselot No. 2800 or of some few Fazioli. I should like to linger a little more on a few of the pianos mentioned above. Let us start chronologically with Pape's pianos:

|

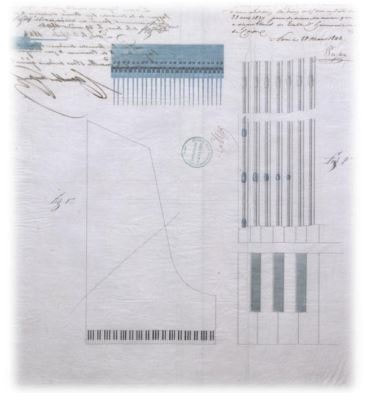

Addition to patent 1BA6100 of 1837 concerning a new mechanism, layout of sounding board and case, filed by JeanHenri Pape on 29 mars 1842. Fonds d'archives INPI, Paris.

|

The patent of addition for eight-octave pianos by Jean-Henri Pape was filed in March 1842 and his first pianos were built in 1844. Nobody knows exactly how many he made. We only know that there were at least two of them. However, they are mentioned in several newspaper articles, one of which in the music journal Le Ménestrel No. 535, of April 14 1844. This article, written by the director of the Brussels conservatory, François Fétis, is most certainly the most complete and interesting about those pianos. It reads as follows : ‘Without supporting the ever growing range that some piano makers give to their instruments, M. Pape felt it necessary to set limits in order to put an end to the continuous change in those instruments. […] At this stage, it may be said that the tonal range of the piano has reached its last limits.’ We shall see later that this quotation is still very important today. In the same article, M. Fétis also depicts a concert for an eight-hand formation, on two eight-octave pianos, in a work by the German pianist and composer Johann Peter Pixis, played by Pixis himself, accompanied by George Osborne, Edouard Wolff and Jakob Rosenhain.

|

Another article, by Hector Berlioz's hand, was published in the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires of June 23 1844. He makes a review of the musical part of the great Industrial Exhibition. Unlike Fétis, he only mentions one single “precious eight-octave piano”. Those pianos are already provided with little removable boxes used to hide the extra notes. The hammers in these pianos strike the strings from above, like the majority of pianos made by Pape in those days.

Little is known about the Érard piano model 3ter No. 51700, except that its manufacturing process was completed in April 1878(3) (that is about thirty years before the first Imperial model) and that is was presented at the Paris Exposition Universelle that same year(4). Franz Liszt certainly played this piano for he was a member of the jury as honorary president. He even was Mme Érard's guest during his short stay in Paris(5). That piano was made as a response to those built by the threatening American competition, for instance by the Chickering and Steinway firms. In order to rival them, it is provided with duplex scale and very fine cabinet work. Unfortunately, it is not known where this piano's ambitus starts and ends. According to the manufacturing records, we know it has 97 keys. It was sold four years later to the firm Allan & Co in Melbourne, Australia, a famous music seller. It is recorded in The Music Sellers by Peter Game, that Allan sold his home and contents on the eve of the great financial crash of 1892. This is verified via auction documents that record it's passing to the White family at The Towers mansion in Toorak, Victoria. The piano is recorded again in auction documents and it's whereabouts has been a mystery since around 1915. .

Little is known about the Érard piano model 3ter No. 51700, except that its manufacturing process was completed in April 1878(3) (that is about thirty years before the first Imperial model) and that is was presented at the Paris Exposition Universelle that same year(4). Franz Liszt certainly played this piano for he was a member of the jury as honorary president. He even was Mme Érard's guest during his short stay in Paris(5). That piano was made as a response to those built by the threatening American competition, for instance by the Chickering and Steinway firms. In order to rival them, it is provided with duplex scale and very fine cabinet work. Unfortunately, it is not known where this piano's ambitus starts and ends. According to the manufacturing records, we know it has 97 keys. It was sold four years later to the firm Allan & Co in Melbourne, Australia, a famous music seller. It is recorded in The Music Sellers by Peter Game, that Allan sold his home and contents on the eve of the great financial crash of 1892. This is verified via auction documents that record it's passing to the White family at The Towers mansion in Toorak, Victoria. The piano is recorded again in auction documents and it's whereabouts has been a mystery since around 1915. .

|

It was around the end of the 19th century, while he was working on Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue for organ BWV 582 in C minor, that the Italian pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni had the incredible idea of suggesting Bösendorfer to build a concert piano that could play the notes corresponding to the 32-feet pipes of an organ. The first prototype of the Imperial model was built in 1892. It was then perfected until judged satisfying and mass production began in 1900. At first, additional keys were hidden beneath a small hinged panel before using a black key cover. Thus, these keys appeared at the same time as the piano, for the Imperial model did not exist before(6) . Bösendorfer has always boasted having built the first eight-octave pianos, but as we have seen above, Pape's piano of 1844 and Érard's of 1878 were made earlier.

|

Extra-keys of Bösendorfer Imperial |

The Érard No. 80774 was manufactured in 1900 and registers indicate that it has 97 notes, from C to C. Curiously enough, the manufacturing of this piano ended the same year when the production of the Imperial model began, and a few months before the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Could Érard have heard Busoni's request? This is not unlikely. Although Érard was present, more than ever, at the Exposition Universelle of 1900, the jury's report did not devote a single line to this piano. Besides, here is how that report reads(7): ‘The Reporter is not expected to review the nearly three hundred pianos gathered in the Champ-de-mars and in the Invalides galleries. […] He only must mention the French or foreign firms which have brought some modification to the instrument's mechanism, or which stand out thanks to particular research in manufacturing.' Even though this is impossible, I still would have liked to get a detailed report on these three hundred pianos! Perhaps this model simply was not presented? I strongly doubt it. In any case, it was sold two years later to one Monsieur Louis Mors in Paris and then, no one heard about it...

Extra-keys of Bösendorfer Imperial So much for the blessed time when piano makers acted in relation to musicians and vice versa. In those days, there were important exchanges between both parties, and the examples of the Imperial model is particularly striking. This piano still has the merit of existing. Today, you can listen to a recording of Oscar Peterson playing jazzified Bach while using those famous additional notes, as Busoni did a hundred years before. Here is a beautiful story that inspires me and that should have inspired some piano makers too.

Extra-keys of Bösendorfer Imperial So much for the blessed time when piano makers acted in relation to musicians and vice versa. In those days, there were important exchanges between both parties, and the examples of the Imperial model is particularly striking. This piano still has the merit of existing. Today, you can listen to a recording of Oscar Peterson playing jazzified Bach while using those famous additional notes, as Busoni did a hundred years before. Here is a beautiful story that inspires me and that should have inspired some piano makers too.

How and why did the piano's ambitus increase?

Are the 88 notes of the modern piano a mere physical result of the opportunities granted by piano strings, combined with a request from composers? This was most certainly true until the 1880s. The broadening of the keyboard's range depends on two very important parameters:

The first one concerns the progress of industry, notably in the field of metals. The piano has always followed the constant evolution of its main sound component: the string. From the 1820s onwards, string makers managed to make steels which got stronger and stronger. Pianos used those strings whose diameter grew increasingly large and whose length kept increasing in order to gain power and length of sound. Therefore, reinforcing metal bars were needed in order to resist the tension of the strings which was also increasing. The first fortepianos had a much lower tension, rather irregular iron or brass strings, whose breaking point was rather low. Thanks to the industrial revolution, and to the progress in metallurgy and steel industry, it became possible to make steels that were more homogeneous, harder, with a higher breaking point, allowing thus the ambitus to increase.

The second important factor, which is not to be neglected, is the demands from pianists and especially from composers. Indeed, piano makers would never have had the idea of building an instrument with so many notes if there had not been such a request. Let us not forget that these manufacturers were here to serve musicians. They built instruments in their interests, which were meant for them only. By reading the various letters written by Beethoven and Liszt, we notice that these two musicians have always complained about the poor technical possibilities imposed by their instruments: lack of power, of response, a range that was too small... It were these complaints, combined with industrial progress, that made music instruments evolve. If those two parameters are not present, the range of the keyboard may hardly increase any more.

In 1880, as the piano finally reached 88 notes, we can indeed assume that it was the mere result of those two parameters. Technical possibilities made it rather hard to go further and most composers were satisfied with it. Nevertheless, if the keyboard's range does not evolve for several years, pianists quickly settle into their habits. The more you wait, the more these habits become hard to change, for pianists as well as for builders. This probably explains the stagnation that has been observed for about 130 years.

Today, however, these 88 notes may be called into question, since it is physically possible to go much further and demand from composers is starting up again little by little, as we shall see later.

The first one concerns the progress of industry, notably in the field of metals. The piano has always followed the constant evolution of its main sound component: the string. From the 1820s onwards, string makers managed to make steels which got stronger and stronger. Pianos used those strings whose diameter grew increasingly large and whose length kept increasing in order to gain power and length of sound. Therefore, reinforcing metal bars were needed in order to resist the tension of the strings which was also increasing. The first fortepianos had a much lower tension, rather irregular iron or brass strings, whose breaking point was rather low. Thanks to the industrial revolution, and to the progress in metallurgy and steel industry, it became possible to make steels that were more homogeneous, harder, with a higher breaking point, allowing thus the ambitus to increase.

The second important factor, which is not to be neglected, is the demands from pianists and especially from composers. Indeed, piano makers would never have had the idea of building an instrument with so many notes if there had not been such a request. Let us not forget that these manufacturers were here to serve musicians. They built instruments in their interests, which were meant for them only. By reading the various letters written by Beethoven and Liszt, we notice that these two musicians have always complained about the poor technical possibilities imposed by their instruments: lack of power, of response, a range that was too small... It were these complaints, combined with industrial progress, that made music instruments evolve. If those two parameters are not present, the range of the keyboard may hardly increase any more.

In 1880, as the piano finally reached 88 notes, we can indeed assume that it was the mere result of those two parameters. Technical possibilities made it rather hard to go further and most composers were satisfied with it. Nevertheless, if the keyboard's range does not evolve for several years, pianists quickly settle into their habits. The more you wait, the more these habits become hard to change, for pianists as well as for builders. This probably explains the stagnation that has been observed for about 130 years.

Today, however, these 88 notes may be called into question, since it is physically possible to go much further and demand from composers is starting up again little by little, as we shall see later.

Is it still possible to add extra notes today?

Bass:

At first, one must know that from a theoretical point of view, it is possible to go down infinitely in the bass register. The only limit is human aesthetics. There are no physical limits, it is possible to make strings endlessly longer and thicker. In general, piano soundboards do not resonate frequencies below 50/60 Hz (which approximately corresponds to the fourth partial of C0 ). Therefore, it is the difference between partials that allows the ear and the brain to reconstruct and to perceive them. Nothing prevents a manufacturer to build a thousand-note piano, only in the bass with strings that would be several tens of meters long and thick.

In practice, it is a little more complicated. The lower the notes, the thicker the string needs to be if we don't want to end up with a piano that would be much too large. This means wrapping the string by winding a copper (or iron, or brass, etc.) wire around it. When the diameter becomes too large, we add a second wire around the first one: this is called double winding or double wrapping. It is perfectly possible to repeat that operation endlessly. However, starting from triple winding, the sound becomes really unintelligible. To me, nine extra notes in the bass register can only be added on a concert piano or on a semi-concert grand, not on smaller instruments. Nonetheless, it is perfectly possible to add only four extra notes (until F0 , for instance) on a smaller piano, even on an upright.

In practice, it is a little more complicated. The lower the notes, the thicker the string needs to be if we don't want to end up with a piano that would be much too large. This means wrapping the string by winding a copper (or iron, or brass, etc.) wire around it. When the diameter becomes too large, we add a second wire around the first one: this is called double winding or double wrapping. It is perfectly possible to repeat that operation endlessly. However, starting from triple winding, the sound becomes really unintelligible. To me, nine extra notes in the bass register can only be added on a concert piano or on a semi-concert grand, not on smaller instruments. Nonetheless, it is perfectly possible to add only four extra notes (until F0 , for instance) on a smaller piano, even on an upright.

Treble :

In 2011, Stephen Paulello put on the market a new type of string called “XM”, whose breaking load is superior to type M or to Röslau type which are currently in use. This value is close to 3000 Newton per mm² for diameter 13, which means that it is possible to hang 300 kilograms on a area of a square millimetre without the string breaking.

However, the higher this value, the less the string will tolerate bending and torsion. For instance, it is impossible to make a French loop with type XM without the string breaking. In 1893, the string maker Poehlmann already developed a steel whose breaking load also reached 3000N/mm². Other tests were carried out with even stronger steels, but the strings would break like glass under the slightest bending, which makes them absolutely impossible to use. Type XM is a compromise between a high breaking load and a bend allowance that makes it usable. It reaches the limits of what is feasible with a piano string. The main motivation for its development is to solve problems related to the breaking of over-solicited strings, especially in the treble and in the bichord section of the bass, or to improve reliability for pianos that are used intensively in music schools. This type of string also enables to extend speaking length during the manufacturing process in order to increase power and sound length. Finally – and that is our interest here – it also allows to expand the ambitus in the extreme treble range. The latter is more delicate than the extreme bass area because of the high tensions and solicitations applied to it.

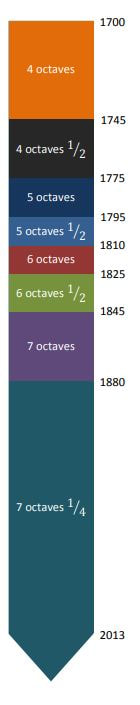

Since Type XM has been marketed, it is possible to get even higher in the treble. But how long can we go up? From a theoretical point of view: infinitely; from a “reasonable” and practical point of view: up to B8 , the B which is an octave above the last B of a standard piano. We are here at the boundaries of extension possibilities for this instrument, not with 97 notes, nor 102, but 108. Thus you can know for the first time the maximum possible range for this instrument using only steel strings.

However, the higher this value, the less the string will tolerate bending and torsion. For instance, it is impossible to make a French loop with type XM without the string breaking. In 1893, the string maker Poehlmann already developed a steel whose breaking load also reached 3000N/mm². Other tests were carried out with even stronger steels, but the strings would break like glass under the slightest bending, which makes them absolutely impossible to use. Type XM is a compromise between a high breaking load and a bend allowance that makes it usable. It reaches the limits of what is feasible with a piano string. The main motivation for its development is to solve problems related to the breaking of over-solicited strings, especially in the treble and in the bichord section of the bass, or to improve reliability for pianos that are used intensively in music schools. This type of string also enables to extend speaking length during the manufacturing process in order to increase power and sound length. Finally – and that is our interest here – it also allows to expand the ambitus in the extreme treble range. The latter is more delicate than the extreme bass area because of the high tensions and solicitations applied to it.

Since Type XM has been marketed, it is possible to get even higher in the treble. But how long can we go up? From a theoretical point of view: infinitely; from a “reasonable” and practical point of view: up to B8 , the B which is an octave above the last B of a standard piano. We are here at the boundaries of extension possibilities for this instrument, not with 97 notes, nor 102, but 108. Thus you can know for the first time the maximum possible range for this instrument using only steel strings.

Keyboard of 108 keys

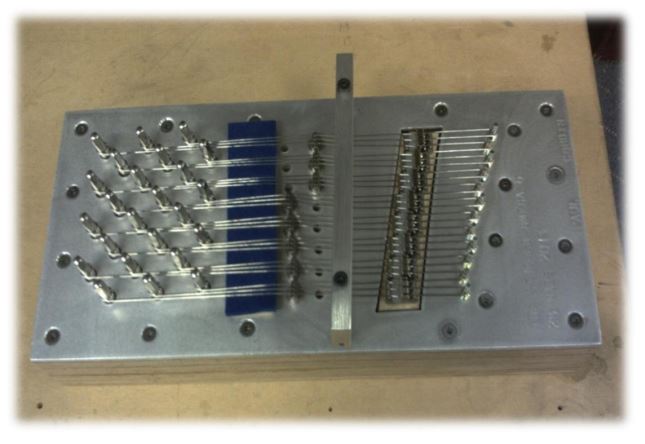

Omega 6

Where does this B come from? Why are we limited to this note? What happens if we get higher?

First of all, a keyboard with 108 keys encompasses nine octaves minus one note. All keys are thus present nine times along the whole keyboard. This also is a rational limit of what can be made with steel strings. To reach this last B, it is necessary to use Type XM in diameter No. 13 (0.775 mm), and its speaking length must not exceed 30 millimetres. If you combine all this, you can tighten the strings until you get to that B8 , without breaking. If we enter all this data in a spreadsheet, we observe that this note is solicited around 87% with a 440Hz tuning. If we continue to add extra notes, strings get solicited between 90% and 100%. The risk of breaking becomes much too high, and if for any reason the piano is to be tuned to a 445 Hz pitch, it is necessary to keep a minimum safety margin. It is still possible to shorten the speaking length of the string, but then it will be difficult for the hammer to strike it without getting stuck against the soundboard. It is still possible to slant the bridge, to shorten the board in order to allow the hammer more space, etc... but above that limit, manufacturing problems pile up and become hard to solve. Even though it is theoretically possible to go up for ever and ever, 108 notes represent a practical limit which becomes hard to overcome. This B8 is thus a result of all those parameters.

But what proves that all these figures apply and actually work? How certainly can we declare that strings will really resist?

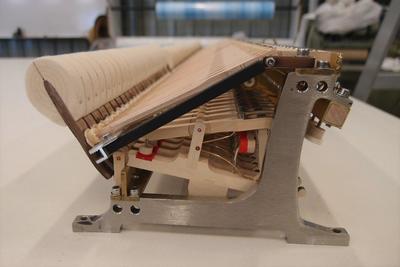

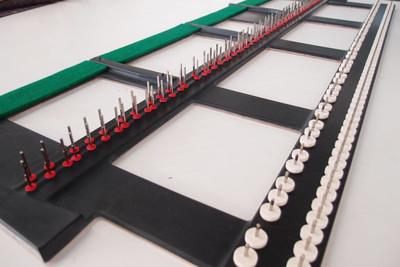

After my visiting the Stuart & Sons firm, its director, Wayne Stuart, suggested that I should write an article about the need for increasing the piano's tonal range and that I should make a prototype of harmonic structure using Type XM, which would only include the highest treble notes. Thanks to their team, we were able to develop this prototype which was named Omega 6. Considering the time that was allowed to me, it was impossible to develop a single piece cast iron frame. Therefore, we used a multi-layered wooden frame covered with an aluminium plate. Omega 6 uses most of the components used in Stuart & Sons' pianos: bridge agraffes, agraffes for the front duplex bridge, ceramic capodastro, adjustable hitch pins, etc.

First of all, a keyboard with 108 keys encompasses nine octaves minus one note. All keys are thus present nine times along the whole keyboard. This also is a rational limit of what can be made with steel strings. To reach this last B, it is necessary to use Type XM in diameter No. 13 (0.775 mm), and its speaking length must not exceed 30 millimetres. If you combine all this, you can tighten the strings until you get to that B8 , without breaking. If we enter all this data in a spreadsheet, we observe that this note is solicited around 87% with a 440Hz tuning. If we continue to add extra notes, strings get solicited between 90% and 100%. The risk of breaking becomes much too high, and if for any reason the piano is to be tuned to a 445 Hz pitch, it is necessary to keep a minimum safety margin. It is still possible to shorten the speaking length of the string, but then it will be difficult for the hammer to strike it without getting stuck against the soundboard. It is still possible to slant the bridge, to shorten the board in order to allow the hammer more space, etc... but above that limit, manufacturing problems pile up and become hard to solve. Even though it is theoretically possible to go up for ever and ever, 108 notes represent a practical limit which becomes hard to overcome. This B8 is thus a result of all those parameters.

But what proves that all these figures apply and actually work? How certainly can we declare that strings will really resist?

After my visiting the Stuart & Sons firm, its director, Wayne Stuart, suggested that I should write an article about the need for increasing the piano's tonal range and that I should make a prototype of harmonic structure using Type XM, which would only include the highest treble notes. Thanks to their team, we were able to develop this prototype which was named Omega 6. Considering the time that was allowed to me, it was impossible to develop a single piece cast iron frame. Therefore, we used a multi-layered wooden frame covered with an aluminium plate. Omega 6 uses most of the components used in Stuart & Sons' pianos: bridge agraffes, agraffes for the front duplex bridge, ceramic capodastro, adjustable hitch pins, etc.

Omega 6 Prototype

|

Omega 6 is not only a family of fatty acids that are found in meat and vegetable oils, but also a small piano harmonic structure at a scale of 1:1, consisting of the last six notes to extend the keyboard from 102 to 108 keys, plus two that already exist. Why this name? Omega (Ω) is the last letter of the Greek alphabet, in contrast with Alpha. It is notably used to indicate an end or limits. Number 6 stands for the six remaining notes (F#, G, G#, A, A#, B). Omega 6 has a small soundboard of about 10 cm², a bridge, a string, a capodastro, tuning pins, etc. The object is around 20 x 40 cm in dimensions and weighs 3.8 kg. The tension is 90 kg on the last string and 1.8 ton on the whole little structure. Omega 6 aims at illustrating figures with a real object. Its manufacturing process was completed on 28 March 2013 and no string has broken so far. By plucking the strings, you can thus hear for the very first time the ultimate frequencies that you may hear on a piano.

|

Bridge Agraffes |

Generally, it is at this moment that readers are the most perplexed.

Sound result

Of course the sound of the extra notes is not unremarkable. On an 88-note piano already, one can notice that the tone of extreme bass notes becomes more and more difficult to perceive, especially when the piano is short. Theoretically, the better-designed the piano, the better the extreme notes. I should like to express a personal opinion on this sound quality. Let me specify that I am not sharing profits with any brand, and that I haven't got any 108-key piano to sell. This opinion is strictly personal and does not commit anyone but me. Nonetheless, I shall try to be as unbiased as possible.

The bass:

|

Obviously, one cannot expect the same clarity or the same purity as with a note from the medium range. The sound quality of extreme bass depends much on the builder and on the desired sound aesthetic. For instance, the aesthetic of the Bösendorfer's extreme bass is famous for its uniqueness. These notes vibrate a great deal, their sound is rich and brassy, sometimes a little hard. Yet, in the extreme bass, one may tend to wish for the contrary, that is a minimum of overtones, since the fundamental becomes much more difficult to make out than in the medium register. One current problem is that most pianists and piano technicians judge the sound quality of extreme bass notes with the Imperial model in mind. Still, we should not judge according to this reference but according to the possible results of developing the concept further.

|

The lower you get in the bass, the more the fundamental disappears. In fortissimo playing, you get a great many harmonics, in which the fundamental gets completely lost. However, if you play them chromatically, you can curiously recognise the note's name with no difficulty. If the aim is not to create a sound effect, whatever it is, the best result is found in pianissimo playing. In softer playing, overtones are less present and you can easily recognise the fundamental of the very first C if you play it together with its upper octave, for instance.

he first G or G# of a standard keyboard is rather high (the first note of the piano being an A). They are respectively the 11th and the 12th key. Their frequency lies around 50 Hz. When you play in these keys, you cannot fully enjoy the depth and power of the piano, for the first bass notes are not low enough. Some feelings, some ideas are thus more difficult to convey. If you have extra bass notes, the G and G# are waiting for you, and a whole new world is opening to you. This is a bit like a secret reserve from which you can draw whenever you like. When I am playing one of these pianos, I feel secure, I know that I can always go further, lower, give more power, or trigger a totally unexpected sound effect. These are notes that certainly require some learning and that should not be used exactly the same way as the other notes on the keyboard. Once more, I insist that all this only applies to a concert instrument. It would be totally ridiculous to make a 105-cm upright piano with 108 keys

he first G or G# of a standard keyboard is rather high (the first note of the piano being an A). They are respectively the 11th and the 12th key. Their frequency lies around 50 Hz. When you play in these keys, you cannot fully enjoy the depth and power of the piano, for the first bass notes are not low enough. Some feelings, some ideas are thus more difficult to convey. If you have extra bass notes, the G and G# are waiting for you, and a whole new world is opening to you. This is a bit like a secret reserve from which you can draw whenever you like. When I am playing one of these pianos, I feel secure, I know that I can always go further, lower, give more power, or trigger a totally unexpected sound effect. These are notes that certainly require some learning and that should not be used exactly the same way as the other notes on the keyboard. Once more, I insist that all this only applies to a concert instrument. It would be totally ridiculous to make a 105-cm upright piano with 108 keys

The treble:

|

As I mentioned earlier, as I am writing these lines, the only pianos with extra treble notes are the Stuart & Sons pianos. I am one of the few French people who have been lucky enough to play them, to adjust and tune them directly on the spot. I have been very happily surprised with the resulting sound quality. The last F 8 (the 102nd key) is far clearer that many a C 8 on standard pianos. First of all, things have to be put into perspective: this note’s frequency is around 5700Hz and the last B (the 108th key) would end up around 8200 Hz according to the chosen pitch and to the piano's tuner. Most organs go up to 12000Hz without any problem, with pipes that are less than a foot long. These registers are mostly used to embellish the sound, notably in the mixture and cymbal stops. I absolutely think that the last notes can be used in the same way.

|

A feature of extreme treble notes is to improve significantly the quality of lower notes. Because of their very short speaking length, they behave a bit like a duplex scale. They enrich very clearly and very beautifully the notes below them by creating a sympathetic vibration. The C7 becomes, thus, totally intelligible. By adding notes in the extreme registers, whatever they may be, you move the usual notes away from the edge of the bridge. The closer the note is from the edge of the bridge, the less convincing the sound result will be, so even if they are not used, the last strings add a considerable sound quality to the rest of the piano.

Finally, tuning these last notes (in the treble as well as in the bass) is easier than one might thing because of their tolerance to precision that is quite relative, even for unisons. The closer you get to the last notes, the more tuning becomes “easy” again.

Finally, tuning these last notes (in the treble as well as in the bass) is easier than one might thing because of their tolerance to precision that is quite relative, even for unisons. The closer you get to the last notes, the more tuning becomes “easy” again.

Repertoire

|

The repertoire for this kind of tessitura remains scarce. Nevertheless, it is only waiting to be composed! It is hard to tell precisely which works have been written for more than 88 notes. Even though composers used to write additional notes on their scores in the past, the editions we have today do not have them any more, in order to be playable on any keyboard. Sometimes, octaviated notes are not indicated, or added as options. Sometimes, we can easily think that if the composer had had enough notes on his piano at a given moment, he would have written higher or lower. The example of Ravel's Piano Concerto in G major is striking. Even though Ravel knew very well the 90-note Érard pianos, the scores we have today indicate a low A when all members of the orchestra play a G.

|

Last bar of Ravel's Concerto in G Major |

It is not unlikely either that some composers would have chosen the key for their compositions according to their piano's tonal range. For instance, Grieg's Piano Concerto and Saint-Saëns' Second Piano Concerto both use the first low A of the keyboard in a spectacular way in their introduction. The composition's key may have been chosen in order not to be restricted by the ambitus.

The works requiring the extra treble notes are more scarce than the ones requiring extra bass notes. We may name Scriabin's 6th Piano Sonata, the pieces played by J. Pixis on Pape pianos, or some contemporary pieces with Kaikhosru Sorabji and Artur Cimirro, notably. According to Bösendorfer, for the bass register, there could be Bartók's Concertos No. 2 and 3, many piano transcriptions by Busoni, of course, as well as his Concerto for piano and male choir, La Cathédrale Engloutie by Debussy, the last movement from Moussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition (The Great Gate of Kiev), Jeux d'eau, Gaspard de la nuit and Une Barque sur l'océan by Ravel...

Oscar Peterson playing an Imperial model |

Finally, extra notes are mainly used for improvisation and in unwritten music in general. Chick Corea, Oscar Peterson, Fazil Say or Stevie Wonder all have improvised on an Imperial model using the extra bass keys. Improvisers are the few pianists who are not too reluctant yet about the idea of adding extra keys to their piano. |

What purpose? What interest? What criticism?

Here is the question that interests us most: is it necessary to add twenty notes to the current piano? What is the use of such a thing? Here is a little experiment:

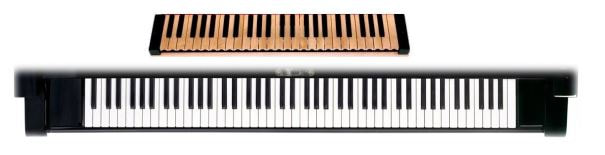

Take two small brightly-coloured objects and put them on the first and last note of a standard keyboard. Now look at the centre of the keyboard (between the E and the F under the brand name). Normally, you can see the two objects in your field of vision without having to look sideways. Now take these two objects and place them against the side arms, outside but still visible. That distance corresponds approximately to a 108-key keyboard. Look at the centre of the piano again. Now the objects get out of your field of vision. With a 108-key keyboard, you cannot see the last notes. You have a horizon of keys in front of you. That is the main criticism from pianists to extended keyboards.

It is true that additional keys are disturbing; it would be a lie to tell the contrary. Nonetheless, I do not think this is a problem at all, quite the opposite. Playing the piano is a hard job, I admit it. Adding twenty notes means adding difficulty. These notes need a time of adaptation, but it is worth the effort. In order to compensate for that difficulty, Pape, Bösendorfer and Petrof had added removable systems that hide the extra notes. That is an idea which I find preposterous, especially from Pape who used to build his pianos at a time when the keyboard's range was constantly evolving. Even worse, Bösendorfer has been putting a black cover on the extra keys. It is as if the manufacturer was apologising, as if every key was saying: 'forgive me for being here, please don't play me'. When Beethoven was offered a six-octave Broadwood in 1817, on the one hand this wasn't enough for him, on the other hand the additional keys were not painted in black. Imagine what Liszt must have put up with during his tours. The variety of pianos was ten times larger than today, perhaps. Liszt would switch from a Viennese piano to a concert Érard, a Boisselot parlour grand, Pleyel pianinos in Parisian boudoirs... It was certainly more difficult to perform a recital in the 19th century than today. All pianists from that time had to adapt, as today's organists, harpsichordists, forte-piano players or percussionists still have to adapt.

I also think that it is vital to increase the ambitus on both sides. This allows to always keep the same symmetry (between the 44th and the 45th note on a standard piano). If you put all the extra notes in the bas, you end up with an unbalanced piano, as it is the case with the Bösendorfer. Above all, a keyboard of 108 keys allows to expand the musical possibilities for improvisers and composers by pushing out of the field of vision the black blinkers of the key blocks and side arms. Among the fears that can be heard, some people claim that the arms are too short for such a large range. I shall answer this by saying that a 1m60-tall person can perfectly play at the same time the first and the last note of a 115-key keyboard. Anyway, nobody forces the pianist to play the first and the last note of the keyboard at the same time. Generally, nobody even forces pianists to play these notes. Do you really think that a composer could be vicious enough to write at both ends of a 108-note piano?

There are many music instruments whose price is notably proportional to their ambitus. This is the case, for instance, of percussion instruments (glockenspiel, marimba, celesta...), harps, or accordions, whose price is determined, among other things, by their tonal range, their registers, the number of ranks or the number of bass notes. Some wind instruments have an extra key, piston valve or barrel in accordance with their price, in order to extend their range in the bass register. It was also the case for some piano manufactures in the 19th and 20th centuries. On the Érard catalogue of 1932, we can see a model 4 upright piano (1m27) with seven octaves, a model 0 baby grand (1m80) with 7¼ octaves, and a concert model No. 3 (2m60) with seven ½ octaves; same for Ibach. A few years earlier, Pleyel used to follow the same principle with pianinos. Until recently, some brands still offered 85 notes on small pianos. Bösendorfer offers three types of keyboards: 88, 92 and 97 according to the model and the price.

Maybe the piano should follow this path today? For the same brand, the bigger the instrument would be, the more notes it would have. Is it normal to have to same tonal range on a baby grand as on a concert model? Should not the price take into account the extension of the ambitus, as it is the case in many musical instruments? To me, pianos' keyboards should extend towards 108 keys as their size and price increase.

Take two small brightly-coloured objects and put them on the first and last note of a standard keyboard. Now look at the centre of the keyboard (between the E and the F under the brand name). Normally, you can see the two objects in your field of vision without having to look sideways. Now take these two objects and place them against the side arms, outside but still visible. That distance corresponds approximately to a 108-key keyboard. Look at the centre of the piano again. Now the objects get out of your field of vision. With a 108-key keyboard, you cannot see the last notes. You have a horizon of keys in front of you. That is the main criticism from pianists to extended keyboards.

It is true that additional keys are disturbing; it would be a lie to tell the contrary. Nonetheless, I do not think this is a problem at all, quite the opposite. Playing the piano is a hard job, I admit it. Adding twenty notes means adding difficulty. These notes need a time of adaptation, but it is worth the effort. In order to compensate for that difficulty, Pape, Bösendorfer and Petrof had added removable systems that hide the extra notes. That is an idea which I find preposterous, especially from Pape who used to build his pianos at a time when the keyboard's range was constantly evolving. Even worse, Bösendorfer has been putting a black cover on the extra keys. It is as if the manufacturer was apologising, as if every key was saying: 'forgive me for being here, please don't play me'. When Beethoven was offered a six-octave Broadwood in 1817, on the one hand this wasn't enough for him, on the other hand the additional keys were not painted in black. Imagine what Liszt must have put up with during his tours. The variety of pianos was ten times larger than today, perhaps. Liszt would switch from a Viennese piano to a concert Érard, a Boisselot parlour grand, Pleyel pianinos in Parisian boudoirs... It was certainly more difficult to perform a recital in the 19th century than today. All pianists from that time had to adapt, as today's organists, harpsichordists, forte-piano players or percussionists still have to adapt.

I also think that it is vital to increase the ambitus on both sides. This allows to always keep the same symmetry (between the 44th and the 45th note on a standard piano). If you put all the extra notes in the bas, you end up with an unbalanced piano, as it is the case with the Bösendorfer. Above all, a keyboard of 108 keys allows to expand the musical possibilities for improvisers and composers by pushing out of the field of vision the black blinkers of the key blocks and side arms. Among the fears that can be heard, some people claim that the arms are too short for such a large range. I shall answer this by saying that a 1m60-tall person can perfectly play at the same time the first and the last note of a 115-key keyboard. Anyway, nobody forces the pianist to play the first and the last note of the keyboard at the same time. Generally, nobody even forces pianists to play these notes. Do you really think that a composer could be vicious enough to write at both ends of a 108-note piano?

There are many music instruments whose price is notably proportional to their ambitus. This is the case, for instance, of percussion instruments (glockenspiel, marimba, celesta...), harps, or accordions, whose price is determined, among other things, by their tonal range, their registers, the number of ranks or the number of bass notes. Some wind instruments have an extra key, piston valve or barrel in accordance with their price, in order to extend their range in the bass register. It was also the case for some piano manufactures in the 19th and 20th centuries. On the Érard catalogue of 1932, we can see a model 4 upright piano (1m27) with seven octaves, a model 0 baby grand (1m80) with 7¼ octaves, and a concert model No. 3 (2m60) with seven ½ octaves; same for Ibach. A few years earlier, Pleyel used to follow the same principle with pianinos. Until recently, some brands still offered 85 notes on small pianos. Bösendorfer offers three types of keyboards: 88, 92 and 97 according to the model and the price.

Maybe the piano should follow this path today? For the same brand, the bigger the instrument would be, the more notes it would have. Is it normal to have to same tonal range on a baby grand as on a concert model? Should not the price take into account the extension of the ambitus, as it is the case in many musical instruments? To me, pianos' keyboards should extend towards 108 keys as their size and price increase.

A composer's opinion

In order to complete this article, I found it interesting to seek for the point of view of a most concerned person. Artur Cimirro is a Brazilian composer, art critic and pianist. He was the first composer in the world who ever composed works for 108-note pianos.

For which purpose du you use additional notes?

First of all, I use them because I precisely don't consider them as additional. When they sit before the 102 keys of a Stuart & Sons, the first thing that pianists do is to press the first and the last key of the keyboard. It seems as if they tried to solve a problem that they don't understand. Why? Because they are not composers. The debate on these “additional” notes only concerns composers (and technicians of course), not pianists.

Were you inspired by the 102 keys of Stuart & Sons or did you use to compose your pieces before knowing those pianos?

My first compositions were written in 1998, and they only require 88 notes. In 2002, I made a transcription of the famous Flight of the Bumblebee by Korsakov. Because of different techniques I used for that piece (octaviated notes, for instance), it was logical to reach the last E* . Later, I changed all the octaves into thirds to make that transcription playable on a standard 88-key piano. Finally, I put the top E again in the latest edition.

Then, in 2006, I started my Sonata Opus 3 that requires the contra C and the top E-flat of the keyboard**, and it is only in 2011 that I heard about the Stuart & Sons pianos for the first time. Three months after the director's invitation, I went to the manufacture to visit it. Just before my leaving, I had composed two pieces requiring 102 keys. In 2012, I visited the factory a second time and it was at this moment that I heard about the new type of string (XM) which allowed to build pianos that wouldn't have 102 keys, but 108. I immediately made changes in my scores and after a few days' work, the first piece for 108-key piano: Eccentric Prelude No. 1, Opus 20. Since that day, some of my other compositions use the whole ambitus and I plan on writing more.

Are you convinced of their interest and necessity?

Absolutely, I hate the sensation of composing for a “half-instrument”, and this is what I feel when I think of 88 notes only. With 108 notes, you have the piano in its practical standards, so this is the standard of the future. Of course, I can compose a piece requiring only 88 keys, I have already done so in some of my compositions, but I prefer to compose a new piece without a minimum nor a maximum of notes in mind.

At the same time, I do not believe that we need more than 108 notes for composing since this is the practical limit of the piano. Thus, I think that everything is in its right place. Cristofori's first forte-piano only had 49 keys (four octaves), and the ambitus gradually increased because it was still very far from its limits. In 1844, when Boisselot & Fils made the first sostenuto pedal, the idea was not welcome, and it was only thirty years later that it was used in Steinway pianos. Today, some people still find it difficult to understand how to use it correctly.

When Beethoven was unhappy with the limits of the pianos of his time, he still wrote his scores with the notes that were missing, and new pianos were built in accordance with this. Today, it is the same but with different pianos and composers.

Other composers such as Liszt, Herz, Pixis, Brahms, Busoni, Ravel, Scriabin... struggled to explore the limits of the piano, and today we have the opportunity to discover the true limits of this instrument in its most complete ambitus. This is a wonderful thing! All those who disagree do not know it yet, but they are doomed to fail, and soon they will be six feet under.

At the same time, I do not believe that we need more than 108 notes for composing since this is the practical limit of the piano. Thus, I think that everything is in its right place. Cristofori's first forte-piano only had 49 keys (four octaves), and the ambitus gradually increased because it was still very far from its limits. In 1844, when Boisselot & Fils made the first sostenuto pedal, the idea was not welcome, and it was only thirty years later that it was used in Steinway pianos. Today, some people still find it difficult to understand how to use it correctly.

When Beethoven was unhappy with the limits of the pianos of his time, he still wrote his scores with the notes that were missing, and new pianos were built in accordance with this. Today, it is the same but with different pianos and composers.

Other composers such as Liszt, Herz, Pixis, Brahms, Busoni, Ravel, Scriabin... struggled to explore the limits of the piano, and today we have the opportunity to discover the true limits of this instrument in its most complete ambitus. This is a wonderful thing! All those who disagree do not know it yet, but they are doomed to fail, and soon they will be six feet under.

Conclusion

When I happen, despite myself, to come across some “music” in a supermarket, in a public place, in a taxi, at the hairdresser's, etc., I often think that a three-note piano would be more than enough.

What's the use? Here is certainly what many readers will wonder when they read this article. I have also wondered the same thing and this is legitimate. However, today I can answer that, on the contrary, it is necessary, more than ever, to give this instrument a new boost. Since it was created, the piano has always evolved together with its ambitus and I am still convinced that its evolution can continue only if the ambitus extends, too. Maybe one day, pianists will admit that 88-note pianos are restrained and limited instruments...

This article does not claim to establish a new standard, it would be utopian to think so. How could the piano have 108 notes tomorrow when the vast majority of piano makers have not even gone through the stages of 102, 97, 92 or even 90? Its aim is to inform pianists, technicians, composers and all persons in relation with the piano that it is possible to extend its tonal range and that it is necessary to do so. By writing these lines, I can simply claim to have said so.

Still, I hope and I firmly believe that a new 97-note standard (contra F to top F), as understood by Pape, is wholly conceivable in the future. Unfortunately, today, the piano follows a logic of standardisation. For an idea to spread, it has to be standardised. The advantages of those 97 notes are that they can be placed on any model of piano, from the upright ones (starting from 1m20) to the concert grands, that they do not complicate the building very much and that they allow to extend the keyboard in an intelligent and reasonable manner. I sincerely hope that I will be able to see that standard developed during my professional career.

All conditions are now gathered to build pianos with a larger tonal range. Here is some interesting musical progress that will leave no pianist or composer indifferent. All this is relatively new, I admit it. The technical means to get there are very recent and this article comes just after. It is important that all this information get clearer in people's minds. Don't we have the opportunity to blow the dust off the situation in which this instrument has been stuck for far too long? Just like you, I am a technician, I do the same job as yours and my main professional motivation is for the profession and for the piano world in general to be going well. I am not interested in megalomania, overgrowth or exploit for the sake of exploit. I have struggled to write this article in the most sincere way, with the sole purpose to serve my profession and music..

What's the use? Here is certainly what many readers will wonder when they read this article. I have also wondered the same thing and this is legitimate. However, today I can answer that, on the contrary, it is necessary, more than ever, to give this instrument a new boost. Since it was created, the piano has always evolved together with its ambitus and I am still convinced that its evolution can continue only if the ambitus extends, too. Maybe one day, pianists will admit that 88-note pianos are restrained and limited instruments...

This article does not claim to establish a new standard, it would be utopian to think so. How could the piano have 108 notes tomorrow when the vast majority of piano makers have not even gone through the stages of 102, 97, 92 or even 90? Its aim is to inform pianists, technicians, composers and all persons in relation with the piano that it is possible to extend its tonal range and that it is necessary to do so. By writing these lines, I can simply claim to have said so.

Still, I hope and I firmly believe that a new 97-note standard (contra F to top F), as understood by Pape, is wholly conceivable in the future. Unfortunately, today, the piano follows a logic of standardisation. For an idea to spread, it has to be standardised. The advantages of those 97 notes are that they can be placed on any model of piano, from the upright ones (starting from 1m20) to the concert grands, that they do not complicate the building very much and that they allow to extend the keyboard in an intelligent and reasonable manner. I sincerely hope that I will be able to see that standard developed during my professional career.

All conditions are now gathered to build pianos with a larger tonal range. Here is some interesting musical progress that will leave no pianist or composer indifferent. All this is relatively new, I admit it. The technical means to get there are very recent and this article comes just after. It is important that all this information get clearer in people's minds. Don't we have the opportunity to blow the dust off the situation in which this instrument has been stuck for far too long? Just like you, I am a technician, I do the same job as yours and my main professional motivation is for the profession and for the piano world in general to be going well. I am not interested in megalomania, overgrowth or exploit for the sake of exploit. I have struggled to write this article in the most sincere way, with the sole purpose to serve my profession and music..

Paul Corbin

[email protected]

[email protected]

(1) Le piano de style en Europe: des origines à 1850, Pascale Vandervellen, Mardaga.

(2) Henri Herz, magnat du piano, Laure Schnapper, Ehess.

(3) Érard Archives, manufacturing registers, Cité de la musique, Paris.

(4) Gustave Chouquet, Exposition universelle internationale de 1878 à Paris. Groupe II. – Classe 13. Rapport sur les instruments de musique et les éditions musicales par M. Gustave Chouquet, Conservateur du Musée du Conservatoire National de Musique, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1880, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Tolbiac, 8-V- 4336.

(5) Liszt et le son Érard, "À la recherche des sonorités perdues", Nicolas Dufetel, Villa Medici Giulini.

(6) http://www.company7.com/bosendorfer.

(7) Ministère du Commerce, de l'industrie, des postes et des télégraphes. Exposition universelle internationale de 1900, à Paris. Rapports du jury international. Classe 17 : Instruments de musique. Rapport de M. Eugène de Bricqueville.

(8) Extra bass notes, Stuart & Sons piano model 220.

(9) Extrêmes-aigus, Stuart & Sons piano model 220.

Thanks to Wayne Stuart, Katie Stuart, Allan Moyes, Stephen Paulello, Jean-Claude Battault, Jérôme Wiss, Hervé Lançon, Lucile Delpon, Artur Cimirro and Ernestine Klesch for their help, their precious advice and their unfailing support.

(2) Henri Herz, magnat du piano, Laure Schnapper, Ehess.

(3) Érard Archives, manufacturing registers, Cité de la musique, Paris.

(4) Gustave Chouquet, Exposition universelle internationale de 1878 à Paris. Groupe II. – Classe 13. Rapport sur les instruments de musique et les éditions musicales par M. Gustave Chouquet, Conservateur du Musée du Conservatoire National de Musique, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1880, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Tolbiac, 8-V- 4336.

(5) Liszt et le son Érard, "À la recherche des sonorités perdues", Nicolas Dufetel, Villa Medici Giulini.

(6) http://www.company7.com/bosendorfer.

(7) Ministère du Commerce, de l'industrie, des postes et des télégraphes. Exposition universelle internationale de 1900, à Paris. Rapports du jury international. Classe 17 : Instruments de musique. Rapport de M. Eugène de Bricqueville.

(8) Extra bass notes, Stuart & Sons piano model 220.

(9) Extrêmes-aigus, Stuart & Sons piano model 220.

Thanks to Wayne Stuart, Katie Stuart, Allan Moyes, Stephen Paulello, Jean-Claude Battault, Jérôme Wiss, Hervé Lançon, Lucile Delpon, Artur Cimirro and Ernestine Klesch for their help, their precious advice and their unfailing support.

Location |

|